The Case for Pronatalism Through Homesteading in Antigua, Guatemala

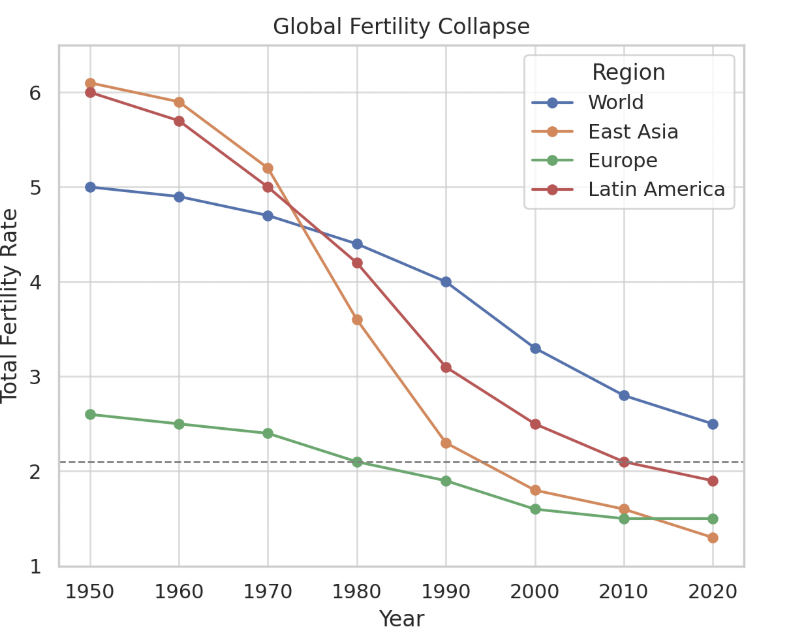

Across the globe, birth rates are collapsing. From Seoul to Stockholm, and yes—even parts of Latin America—the Total Fertility Rate (TFR) has slipped well below the replacement threshold of 2.1. This isn’t just a demographic curiosity—it’s an existential alarm. Fewer children today means fewer workers tomorrow, fewer caretakers for the elderly, and a shrinking cultural and economic base for future generations.

They whisper about the birth rate in reports. They chart it in polite PowerPoints. But this isn’t a chart. It’s a collapse. It’s the sound of a civilization fading out like smoke in the wind.

Today, over 70% of countries—including nearly all of Europe, East Asia, and the Americas—have a TFR below replacement level. Many are already experiencing absolute population decline.

But what does that actually mean in real terms? A TFR of 1.0 doesn’t just mean “fewer kids”—it means each generation is literally half the size of the one before. Imagine a village of 1,000 people dwindling to 500, then 250, and so on—through sheer erosion, not catastrophe. Regions with a TFR of 1.7, like much of Europe or China, face slower but equally unstoppable decline: schools shut, classrooms empty, entire towns age into obsolescence. Loneliness becomes systemic. In Japan, close to 25% of women over 65 have no surviving children, and “kodokushi”—deaths alone—now number in the tens of thousands annually.

Here are some facts about the crisis worldwide:

South Korea’s TFR is just 0.72, projecting population declines from 51 million to under 20 million in 80 years. That’s not a birth rate. That’s a vanishing act.

Japan sells more adult diapers than baby diapers. Some maternity wards are now eldercare centers.

Millions of rural Japanese homes sit vacant—given away or abandoned in ghost villages.

China’s population began shrinking in 2022 and may lose 400 million people by 2100.

Italy closed over 10,000 schools between 2010 and 2020 due to plummeting birth rates.

By 2050, Germany will have more people over 80 than under 20—a demographic first.

Singapore’s fertility rate sits at 1.05, despite aggressive government incentives. A fifth of women remain childless.

Eastern European countries like Bulgaria have lost over 20% of their population since the 1990s.

In Hong Kong, a 1% rise in housing prices correlates with a 0.5% drop in birth rates.

Brazil’s housing lotteries raised childbearing odds by 32% for homeowners aged 20–25.

But this isn’t about data. It’s about decay. Civilizations die in silence—not with war, but with fewer babies and more funerals.

To understand where our trajectory may lead, we need only look to Japan—a nation decades ahead in demographic decline. In rural prefectures across the archipelago, entire towns have hollowed out. Schools closed. Roads overgrown. The elderly die alone, and no children replace them. The land still exists, but the human thread has been severed. These “ghost villages” are not science fiction—they are a sobering preview of what’s to come.

This dystopian vision echoes the film Children of Men (Alfonso Cuaron, 2006), where a global fertility crisis leads to societal collapse, nihilism, and the unraveling of civilization itself. While fiction, it resonates because it reflects the logical endpoint of our current trends: a world unanchored from its future.

And here we are—still talking like city planners. Still acting like it’s all okay if we just build more apartments. But we’re not rats. We’re not meant to live stacked one atop the other in gray little boxes, eating takeout alone.

You can’t raise a family in a shoebox. You can’t teach love through screens. You need space. You need earth. You need sky, and sweat, and a garden to hoe, and a kid to chase through the trees.

But it doesn’t have to be that way.

So what’s the remedy?

Antigua offers a unique setting for a different future. Fertile volcanic soils, a temperate climate, and a deep-rooted cultural emphasis on family make it a natural backdrop for a pronatalist life. Here, families can raise goats, grow food, and build homes with their own hands. More importantly, they can raise children grounded in both purpose and place.

Land ownership is critical in this equation. In cities, the cost of raising a family—rent, childcare, food—makes each additional child a financial strain. But on a homestead, every new family member is also a contributor. With space to build, grow, and dream, families are free to expand—unburdened by the invisible ceilings imposed by urban life.

Empirical evidence supports this. A 2006 study of the Ecuadorian Amazon found that women in households lacking land titles had 27% higher birth rates than those with secure tenure—and each cultivated hectare was linked to a 16% higher fertility rate, even after controlling for education and age. Another cross-national study of 26 developing countries found that landholding patterns positively correlated with rural fertility, supporting the idea that owning and cultivating land helps families thrive.

Homesteading also confronts another barrier head-on: housing constraints. In high-cost urban environments, millions of young adults delay homeownership—trapped in small living units, delaying marriage, and postponing children. One U.S. think tank found that housing costs were the single largest factor preventing people from having children. Across countries, fertility strongly correlates with more spacious dwellings. Houses with yards lead to more births than cramped apartments.

But we don’t need studies. We know it in our bones.

In contrast, owning land on a homestead transforms children into economic assets and spiritual gifts—not burdens. With room to build, grow, and dream, families aren’t limited by the quiet pressure of walls. Even a modest quarter-acre can let children flourish, grandparents visit, and faith take shape in home and hearth.

Pronatalism isn’t just a demographic fix—it’s a values-driven rebellion. It resists disposable consumer culture and stakes a claim in continuity, care, and stewardship. Homesteading in Antigua offers both a home and a mission: raising families rooted in land, meaning, and mutual support.

And in an age when nations are aging into economic and moral stagnation, the humble act of raising a large family on a piece of land becomes an act of civilizational defiance.

The 21st century will belong to those who choose to plant seeds—literal and figurative. Antigua may seem like a small dot on the map, but it could become the cradle of a new kind of future: rooted, resilient, and regenerative.